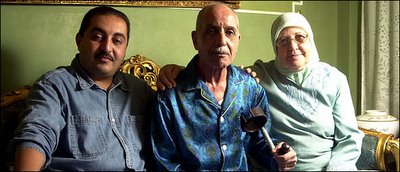

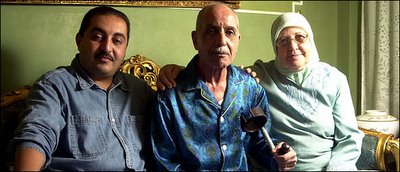

Ehab Elmaghraby in Alexandria, Egypt, with his parents in April 2004. Mr. Elmaghraby, detained after 9/11, said he settled his lawsuit reluctantly.

Ehab Elmaghraby in Alexandria, Egypt, with his parents in April 2004. Mr. Elmaghraby, detained after 9/11, said he settled his lawsuit reluctantly.

New York Times

February 28, 2006

By NINA BERNSTEIN

The federal government has agreed to pay $300,000 to settle a lawsuit brought by an Egyptian who was among dozens of Muslim men swept up in the New York area after 9/11, held for months in a federal detention center in Brooklyn and deported after being cleared of links to terrorism.

The settlement, filed in federal court late yesterday, is the first the government has made in a number of lawsuits charging that noncitizens were abused and their constitutional rights violated in detentions after the terror attacks.

It removes one of two plaintiffs from a case in which a federal judge ruled last fall that former Attorney General John Ashcroft, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other top government officials must answer questions under oath. Government lawyers filed an appeal of that ruling on Friday.

In the settlement agreement, which requires approval by a federal judge in Brooklyn, lawyers for the government said that the officials were not admitting any liability or fault. In court papers they have said that the 9/11 attacks created "special factors," including the need to deter future terrorism, that outweighed the plaintiffs' right to sue.

"A settlement like this is not a precedent, but it's a form of accountability," said Gerald L. Neuman, a law professor at Columbia University who is an expert in human rights law and was not involved in the case. "When the government finds it necessary to settle, that changes the government's incentives. It doesn't mean the government will settle future cases that it makes different calculations about," like another lawsuit, brought as a class action on behalf of hundreds of detainees, that is pending before the same judge.

A spokesman for the Justice Department said officials would not comment on the agreement. But lawyers who represent both the Egyptian, Ehab Elmaghraby, who used to run a restaurant near Times Square, and the second plaintiff, a Pakistani who is still pursuing the lawsuit, described the outcome as significant.

"This is a substantial settlement and shows for the first time that the government can be held accountable for the abuses that have occurred in Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo Bay and in prisons right here in the United States," said one of the lawyers, Alexander A. Reinert of Koob & Magoolaghan.

The lawsuit accuses Mr. Ashcroft and the F.B.I. director, Robert S. Mueller III, of personally conspiring to violate the rights of Muslim immigrant detainees on the basis of their race, religion and national origin, and names a score of other defendants, including Bureau of Prison officials and guards at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn.

A 2003 report by the Justice Department's inspector general found widespread abuse of the noncitizen detainees at the Brooklyn center after 9/11, and in recent months, 10 of the center's guards and supervisors have been disciplined.

Mr. Elmaghraby, who spent nearly a year in detention, and the Pakistani man, Javaid Iqbal, held for nine months, charged that while shackled they were kicked and punched until they bled. Their lawsuit said they were cursed as terrorists and subjected to multiple unnecessary body-cavity searches, including one in which correction officers inserted a flashlight into Mr. Elmaghraby's rectum, making him bleed.

In a telephone interview from his home in Alexandria, Egypt, Mr. Elmaghraby, 38, said he had reluctantly decided to settle because he is ill, in debt and about to have surgery for a thyroid ailment aggravated by his treatment in the detention center.

"I wish I come to New York, to stay in the court face to face with these people," he said in imperfect English, adding that he had always expected the courts to uphold his claim. "I lived 13 years in New York, I see a lot of big cases on TV. I think the judges is fair."

The government had argued that the lawsuits should be dismissed without testimony because the extraordinary circumstances of the terror attacks justified extraordinary measures to confine noncitizens who fell under suspicion, and because top officials need governmental immunity to combat future threats to national security without fear of being sued.

The federal judge, John Gleeson of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, disagreed, writing in his decision last September, "Our nation's unique and complex law enforcement and security challenges in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks do not warrant the elimination of remedies for the constitutional violations alleged here."

In all, 762 noncitizens were arrested in the weeks after 9/11, mostly on immigration violations, according to government records. Mr. Elmaghraby and Mr. Iqbal were among 184 identified as being "of high interest" to investigators and held in maximum-security conditions, in Brooklyn and elsewhere, until the F.B.I. cleared them of terrorist links. Virtually all were Muslims or from Arab countries.

That in itself is not evidence of discrimination, government lawyers wrote in the brief they filed on Friday with the Appellate Division, Second Department, because "the Al Qaeda terrorists who perpetrated the Sept. 11 attacks were Muslims from certain Arab countries" who "viewed themselves as conducting a religious war."

"There were no clear judicial precedents in this extraordinary context," the appeal brief said, calling the policy of holding people until they could be cleared "a bona fide response to a national catastrophe."

Unlike the detainees covered by the class-action lawsuit, who were held on immigration violations alone, Mr. Elmaghraby and Mr. Iqbal eventually pleaded guilty to minor federal criminal charges unrelated to terrorism: Mr. Elmaghraby to credit card fraud, Mr. Iqbal to having false papers and bogus checks. But they maintain that they did so only to escape the abuse. They were deported in 2003 after serving prison terms.

Mr. Iqbal was one of several detainees who returned to New York this year to give depositions in their lawsuits under conditions of extraordinary security, including the requirement that they be in constant custody of federal marshals and not call anybody. Mr. Elmaghraby did not come because of his ill health and because the settlement was close, said one of his lawyers, Haeyoung Yoon of the Urban Justice Center.

"His circumstances made it extremely difficult for him to continue," Ms. Yoon said. "But I also feel this is really the beginning of justice for what happened in New York and the United States after Sept. 11, the mass arrests, detention and basically disappearance of an entire community."

Mr. Elmaghraby, who had a weekend flea market stand at Aqueduct Raceway in Queens, was picked up on Sept. 30, 2001, in his apartment in Maspeth, Queens, when federal agents were investigating his landlord, apparently because years earlier the landlord, also a Muslim, had applied for pilot training. Mr. Elmaghraby says his wife, an American citizen, left him after being threatened with arrest by an F.B.I. agent when she arrived at his first court hearing.

Mr. Iqbal was arrested in his Long Island apartment on Nov. 2 by agents who were apparently following a tip about false identification cards. In his apartment they found a Time magazine showing the World Trade Center towers in flames and paperwork showing that he had been in Lower Manhattan on Sept. 11, picking up a work permit from immigration services.

The inspector general's report said that little effort was made to distinguish between legitimate terrorism suspects and people picked up by chance, and that clearances took months, not days, because they were a low priority. Among the abuses described in the report — many of them caught on prison videotape — were beatings, sexual humiliations and illegal recording of lawyer-client conversations.

After the report was released, Mr. Ashcroft said he made "no apologies" for finding every legal way to protect the public. Still, officials pledged to improve the system and punish abuses.

Traci L. Billingsley, a spokeswoman for the Federal Bureau of Prisons, said that its own investigation began in April 2004, after federal officials declined to prosecute.

She would not identify the 10 employees disciplined, but said that two had been fired and two demoted, and that the others had received suspensions ranging from 2 to 30 days. She listed the offenses as "lack of candor, unprofessional conduct, misuse of supervisory authority, conduct unbecoming, inattention to duty, failure to exercise supervisory responsibilities, excessive use of force, and physical and/or verbal abuse."

Because of the secrecy surrounding the cases, however, the taint of suspicion has been almost impossible for former detainees to dispel, their lawyers said. In one of the court hearings leading up to the return of the former detainees for depositions, for example, the federal magistrate asked what made them different from anyone else suing the government, "other than their ethnicity."

Ernesto H. Molina Jr., a Justice Department lawyer representing Mr. Ashcroft, replied, "That they came under the umbrella of a terrorist investigation, your honor."

Copyright 2006The New York Times Company