Pakistan Earthquake Zone Escapes Dreaded 2nd Wave of Deaths

Washington Post

Washington PostMild Weather, Timely Aid Make Difference

By John Lancaster

March 2, 2006

DANA DAMAN JHOL, Pakistan -- In the first days after the Oct. 8 earthquake, things looked bleak for Sher Zaman's family. They had no food, no shelter -- not even blankets. Those, along with the rest of their meager possessions, had been buried in the rubble of their home, high on a Kashmiri mountainside that the family expected would soon be covered with snow.

But Zaman had no intention of hiking down to a relief camp and abandoning his only remaining wealth, a patch of land and two cows. So he decided to stay. Now, more than four months later, that choice appears to have been vindicated.

Helped by uncommonly mild weather, timely outside aid and a resourcefulness bred of harsh mountain living, Zaman, his wife and four children have been able to put the worst of the catastrophe behind them. Amply supplied with food and medicine, they live in a temporary shelter made from wood scraps and corrugated steel.

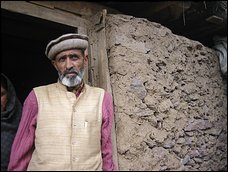

"Allah has been kind," said Zaman, a thin, weather-beaten farmer and retired soldier who says he is about 50 but looks a decade older. "Since our home wasn't intact, Allah realized this and saved us from a severe winter."

The family's experience sheds light on a welcome and somewhat unexpected twist to the aftermath of the earthquake, the worst natural disaster in Pakistan's history, which killed at least 73,000 people and left an estimated 2.8 million homeless across Pakistani Kashmir and parts of northern Pakistan. An additional 1,300 people died in the part of Kashmir held by India.

Despite dire warnings last fall, a widely anticipated second wave of deaths from disease, hunger and exposure has not materialized, according to foreign and Pakistani aid officials. As a result, aid workers are starting to shift their attention from emergency relief to the long-term challenge of reconstruction across a remote mountainous region roughly the size of Belgium.

Besides the good weather, which has enabled helicopters to keep shuttling supplies through the winter, the aid effort owes its success to foreign donors, including the United States, and a surprisingly smooth working relationship between aid groups and the Pakistani army, which has taken the lead in relief operations after a stumbling start.

"I think most of the humanitarian actors on the ground think we're going to make it," said Jan Vandemoortele, the U.N. coordinator for earthquake relief in Pakistan. "We were fearing a second wave of deaths. It didn't occur."

Winter is not over in the Himalayas, and aid officials warn that a heavy snowfall or plunge in temperatures could still threaten survivors. Other worries include a looming shortage of funds for helicopter operations, which cost about $500,000 a day, and the potential for landslides across the unstable terrain.

But in general, the picture looks far brighter than it did in late October.

After a slow start, foreign donors by this month had contributed 68 percent of the $550 million that the United Nations requested to fund emergency relief operations for the six months after the disaster.

Because of a shortfall in the global supply of winter tents, aid agencies have scrambled to provide survivors outside relief camps with makeshift shelters built from salvaged timber, plastic tarpaulins and corrugated-metal sheets. An absence of major snowstorms has made the job much easier.

"We've got the goods out and we're just at this point trying to find the little gaps," said Hugh Smith, a Canadian relief coordinator for the International Organization for Migration in Muzzafarabad, the capital of Pakistani Kashmir. "Allah is on our side."

Donor nations in November pledged nearly $6 billion for long-term reconstruction, exceeding the Pakistani government's goal of $5.2 billion. The United States has pledged or contributed $510 million for relief and reconstruction.

The earthquake destroyed about 400,000 homes -- to say nothing of businesses and public facilities -- and recovery will take years. About 250,000 survivors live in relief camps; the remaining 2.5 million or so have moved in with relatives or remained on their land in temporary shelters.

To prevent the relief camps from turning into permanent slums, aid agencies are drawing up plans to encourage earthquake refugees to return to their towns and villages with the coming of spring. But many have nothing to return to.

Shaheen Faizal lived with her husband, a construction worker, and four children in a village on a hill above Muzzafarabad. Though all survived the earthquake, they lost not only their home but also the ground beneath it, which tumbled down the hill.

Now the family lives in a plastic-covered tent at the sprawling al-Mustafai refugee camp, subsisting on handouts of flour and cooking oil and sharing flimsy latrines with hundreds of other families. The children are enrolled in a UNICEF school at the camp, and Faizal said she does not know when, if ever, they will return to what remains of their village.

"Everything is gone," Faizal, 36, said quietly. "We will stick to this place as long as the camp is here. We have no option. I miss my house -- I miss everything that I had -- but I have to raise my kids. I have to live my life."

Aid workers had initially feared that the refugee population in camps would swell even larger. But an unexpectedly large number of survivors -- between 350,000 and 380,000 -- have stayed in remote areas above the normal winter snow line of 5,000 feet, according to U.N. estimates.

Among them are Sher Zaman and his family, whose village is about 60 miles northeast of Islamabad at an altitude of 7,100 feet. Sitting outside his makeshift home on a warm afternoon, he recalled the terrifying "growling" that knocked him off his feet in the field, then raised huge plumes of dust as mountains shed forested flanks.

Although his family survived, the quake destroyed their mud-and-stone home and the small roadside shop where Zaman sold cigarettes and sugar, leaving them with nothing except their small landholdings and two cows; two others died when their stable tumbled down the mountainside.

After a miserable three nights sleeping outside, the family patched together a flimsy shelter from salvaged timbers and tarpaulins. They lived on dried corn and water from a nearby spring. About a week after the quake, the first outside help arrived when volunteers reached the village on foot. They were from Jamaat ul-Dawa, a radical Islamic group that has played a highly visible role in earthquake relief.

With his cows to feed and a pile of salvaged timber to protect, Zaman said he never gave a second's thought to leaving for one of the new relief camps below. "We would have become permanent refugees," he said.

Gradually, conditions improved. The family built a shelter for the cows, and then one for themselves, using sheets of corrugated metal supplied by Jamaat ul-Dawa. A month ago, Zaman and his two eldest sons finished work on a mud-and-stone hut that now serves as a kitchen, with a clay oven and a stone storage bin for corn.

Every week one of them treks down the mountainside to a relief center to retrieve flour and other staples. They also use the services of a Red Cross medical clinic, which last week treated Zaman's 11-year-old daughter for mild pneumonia. She and his 14-year-old son have returned to school.

A month ago, a government official came to the village to provide each family with $416 in rupees, the first installment on a total payment of $3,000. Zaman hopes to begin work soon on a permanent home made of wood.

In the valley below, almond and apricot trees have already started to bud.

© 2006 The Washington Post Company

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home