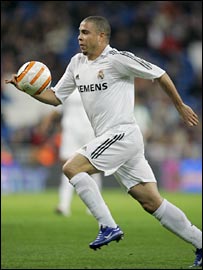

Ronaldo A Saviour?

BBC Sports

BBC SportsMarch 20, 2006

By Tim Vickery

South American football reporter

Ronaldo has frequently mentioned his desire to end his career back in Brazil - specifically with Flamengo of Rio, the club he supported as a boy.

There has recently been speculation that this might happen sooner rather than later.

But if he does move back to his home town, Ronaldo will - as he is surely already aware - find himself in the land that time forgot.

Brazilian football has moved on, and Rio de Janeiro has been left behind.

In the course of the last decade and a half the focus of Brazilian club football has switched from the local to the continental.

The highlight of the year used to be winning the state championship - there is one for each of the 27 states that make up the giant country.

Nowadays attentions are centred on lifting the Copa Libertadores - South America's equivalent of the Champions League.

The importance of the state championships is easy to explain; they represent the tradition of the Brazilian club game.

Brazil is a country the size of a continent. Not until 1971 was the infra-structure in place to stage a genuinely national championship.

So the mystique and the history of the clubs was forged almost entirely in terms of local rivalries. But having big teams play against tiny local rivals on a league basis made little financial sense.

While hyper-inflation reigned it hardly mattered. Clubs could meet their financial commitments simply by paying late.

Then, in 1994, came monetary stability, and Brazilian clubs quickly found out that the real world could be a frightening place.

The state championships still exist, but they have been cut back from a mind-numbing six months to a still over-long three.

They have lost their shine. At worst, they are a complete waste of time. At best, a glorified pre-season tournament.

The national championship has been extended. And the major incentive of the national championship, bigger than the title itself, is the chance to qualify for the Libertadores.

The continental tournament brings in the TV money, the exposure, and, best of all, the possibility of going to Japan to take on the European champions. This year, for the first time, the big three from Brazil's biggest city - Sao Paulo, Corinthians and Palmeiras - are all taking part in the Libertadores.

All of them have hopes of winning. But two sides from the provinces have so far been even more impressive.

Internacional of Porto Alegre have played as well as any side in the 32-team field, and debutants Goias, from the Central West countryside, have won all their games and done so in style.

But from Rio, nothing. Brazil's most traditional football city has missed out on the continental movement.

No team from Rio has qualified for the Libertadores since 2002, when Flamengo finished bottom of their group.

Farcical administration, lack of long-term planning, corruption, unscrupulous deals with agents and head in the sand ignorance have all conspired to undermine football in Rio de Janeiro.

These days when the national championship gets underway the former capital's once great clubs are more often to be found battling against relegation.

On Sunday Flamengo - who boast over 20 million supporters - gave further evidence of their decline when they were knocked out of the Rio State championship after a 2-1 loss to Vasco da Gama.

At least they went down fighting, clashing with their opponents: with the referee and even with the police after the final whistle.

When he does come back Ronaldo will inevitably be seen as a saviour. And if he helps get Rio football back on the right track then nobody can dispute his right to be called 'The Phenomenon'.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home