Clinton, Impresario of Philanthropy, Gets A Progress Update

The New York Times

The New York TimesApril 1, 2006

By CELIA W. DUGGER

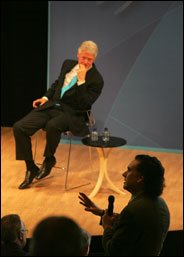

"Ajay, please come up here!" said Bill Clinton, summoning a Citigroup executive, Ajay Banga, to the stage. There, before a full house of corporate chieftains, millionaire investors, nonprofit leaders and assorted more ordinary people, the former president slipped comfortably yesterday into his new role as an impresario of philanthropy.

It was Mr. Banga's turn to bask in the glow of Mr. Clinton's approval. Under the auspices of Mr. Clinton's "global initiative," Citigroup has committed $5.5 million to support financial education for poor people and awards that recognize individuals who create innovative programs to finance very small businesses.

"Mr. President, keep going!" Mr. Banga told Mr. Clinton, and assured him of Citigroup's support. "Three hundred thousand employees are behind you."

The gathering at Jazz at Lincoln Center on Columbus Circle in Manhattan represented six months since Mr. Clinton invented one of the most high-profile ventures of his post-presidency, the Clinton Global Initiative. It brings together people with money, influence and ideas to talk about global poverty, climate change and religious and ethnic conflict.

What sets it apart from other such high-minded conferences is Mr. Clinton's insistence that participants not just discuss these daunting problems but also do something concrete about them — or not be invited back. A staff of four works full-time on "commitments management."

Since the program began with a conference in September, almost 300 corporations, individuals and nonprofit groups have committed more than $2.5 billion to an array of good works, his staff says. Some projects would have happened anyway, but Mr. Clinton estimates that more than half are genuinely new.

"More and more people were saying to me all the time: 'What can I do? What can I do? Tell me something to do,' " Mr. Clinton said in an interview. "I just heard it all the time. So here we are in New York. The United Nations meets here. We can bring together all kinds of people from all over the world. So I just decided to organize a 'What can I do?' conference. And then try to do it every year for a decade."

A parade of people gave testimonials from microphones in the audience about what they had done since they made their commitments in September.

Dr. Bruce Charish, a Manhattan cardiologist, founded a new nonprofit group, Doc to Dock, to send medical tools and supplies to hospitals and clinics in Africa. "Just the prestige of being a C.G.I. commitment has opened many corporate doors," he said.

Maria Otero, who heads Acción, described how her nonprofit group and another, Unitus, have taken steps to fulfill their promise to provide small loans and other financial service to millions of poor people in India by 2015. "I want to thank you for galvanizing us to do this work," she told Mr. Clinton.

Nancy Kete, the director of Embarq, founded with a grant from the Shell Foundation, is working with Porto Alegre, Brazil, to develop mass transit powered by low-polluting buses. "If you care about climate change, you have to care about transportation," she said.

A row of black Mercedeses and Lincolns lined up on West 60th Street as guests arrived yesterday for a breakfast with Mr. Clinton at Dizzy's Club that felt more like a cocktail party, albeit one where only orange juice and coffee were served. A duo played jazz on saxophone and piano, and Mr. Clinton embraced his daughter, Chelsea.

With sweeping views of Central Park, 100 or so people milled about. They were a reflection of Mr. Clinton's vast network. There was Mike Rienzi, an Italian food importer from Astoria, who said Mr. Clinton came to a recent fund-raiser he held for research into deafness, and stayed all evening. Yesterday was his first time at a Clinton Global Initiative event, and he said he had not made any commitment yet. But he added, "Whatever the Clintons do, I support them."

Across the room Bernard Schwartz, chairman of Loral Space and Communications, and Lewis Cullman, 87, a philanthropist, chatted. Both had come to the September meeting and neither had yet picked a project to finance. "I'm ready to do so," Mr. Schwartz said. "I'm sure having said so, I'll get a lot of knocks on my door, and they'll be welcome."

Soon the breakfast guests merged with the 500 people who had come for the main event, an updating on the program's progress. Ami Nahshon, who heads the Abraham Fund Initiatives, a nonprofit group that promotes coexistence between Israel's Jewish and Arab citizens, hopes to find patrons to encourage business development in Arab communities. He seemed very pleased to be at the event. "It feels a bit like philanthropic speed dating," he said.

Mr. Clinton himself chose a retailing metaphor.

"Maybe the model is eBay," he said. "It brings buyers and sellers together. Maybe we can create a massive, floating and flexible partnership where people who want to give some money and people who want to provide services or programs and people who need economic and social support will be together in an ongoing dialogue."

"That would be my dream," he said, "that we could turn the concern of people who are well educated and have good incomes or represent foundations or businesses into action."

Copyright 2006The New York Times Company Home

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home