Women And The World Economy

The Economist

April 12, 2006

A guide to womenomics

The future of the world economy lies increasingly in female hands

“WHY can't a woman be more like a man?” mused Henry Higgins in “My Fair Lady”. Future generations might ask why a man can't be more like a woman. In rich countries, girls now do better at school than boys, more women are getting university degrees than men are and females are filling most new jobs. Arguably, women are now the most powerful engine of global growth.

In 1950 only one-third of American women of working age had a paid job. Today two-thirds do, and women make up almost half of America's workforce (see chart 1). Since 1950 men's employment rate has slid by 12 percentage points, to 77%. In fact, almost everywhere more women are employed and the percentage of men with jobs has fallen—although in some countries the feminisation of the workplace still has far to go: in Italy and Japan, women's share of jobs is still 40% or less.

The increase in female employment in developed countries has been aided by a big shift in the type of jobs on offer. Manufacturing work, traditionally a male preserve, has declined, while jobs in services have expanded. This has reduced the demand for manual labour and put the sexes on a more equal footing.

In the developing world, too, more women now have paid jobs. In the emerging East Asian economies, for every 100 men in the labour force there are now 83 women, higher even than the average in OECD countries. Women have been particularly important to the success of Asia's export industries, typically accounting for 60-80% of jobs in many export sectors, such as textiles and clothing.

Of course, it is misleading to talk of women's “entry” into the workforce. Besides formal employment, women have always worked in the home, looking after children, cleaning or cooking, but because this is unpaid, it is not counted in the official statistics. To some extent, the increase in female paid employment has meant fewer hours of unpaid housework. However, the value of housework has fallen by much less than the time spent on it, because of the increased productivity afforded by dishwashers, washing machines and so forth. Paid nannies and cleaners employed by working women now also do some work that used to belong in the non-market economy.

Nevertheless, most working women are still responsible for the bulk of chores in their homes. In developed economies, women produce just under 40% of official GDP. But if the worth of housework is added (valuing the hours worked at the average wage rates of a home help or a nanny) then women probably produce slightly more than half of total output.

The increase in female employment has also accounted for a big chunk of global growth in recent decades. GDP growth can come from three sources: employing more people; using more capital per worker; or an increase in the productivity of labour and capital due to new technology, say. Since 1970 women have filled two new jobs for every one taken by a man. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that the employment of extra women has not only added more to GDP than new jobs for men but has also chipped in more than either capital investment or increased productivity. Carve up the world's economic growth a different way and another surprising conclusion emerges: over the past decade or so, the increased employment of women in developed economies has contributed much more to global growth than China has.

Girl power

Women are becoming more important in the global marketplace not just as workers, but also as consumers, entrepreneurs, managers and investors. Women have traditionally done most of the household s hopping, but now they have more money of their own to spend. Surveys suggest that women make perhaps 80% of consumers' buying decisions—from health care and homes to furniture and food.

hopping, but now they have more money of their own to spend. Surveys suggest that women make perhaps 80% of consumers' buying decisions—from health care and homes to furniture and food.

Kathy Matsui, chief strategist at Goldman Sachs in Tokyo, has devised a basket of 115 Japanese companies that should benefit from women's rising purchasing power and changing lives as more of them go out to work. It includes industries such as financial services as well as online retailing, beauty, clothing and prepared foods. Over the past decade the value of shares in Goldman's basket has risen by 96%, against the Tokyo stockmarket's rise of 13%.

Women's share of the workforce has a limit. In America it has already stalled. But there will still be a lot of scope for women to become more productive as they make better use of their qualifications. At school, girls consistently get better grades, and in most developed countries well over half of all university degrees are now being awarded to women. In America 140 women enrol in higher education each year for every 100 men; in Sweden the number is as high as 150. (There are, however, only 90 female Japanese students for every 100 males.)

In years to come better educated women will take more of the top jobs. At present, for example, in Britain more women than men train as doctors and lawyers, but relatively few are leading surgeons or partners in law firms. The main reason why women still get paid less on average than men is not that they are paid less for the same jobs but that they tend not to climb so far up the career ladder, or they choose lower-paid occupations, such as nursing and teaching. This pattern is likely to change.

The fairer and the fitter

Making better use of women's skills is not just a matter of fairness. Plenty of studies suggest that it is good for business, too. Women account for only 7% of directors on the world's corporate boards—15% in America, but less than 1% in Japan. Yet a study by Catalyst, a consultancy, found that American companies with more women in senior management jobs earned a higher return on equity than those with fewer women at the top. This might be because mixed teams of men and women are better than single-sex groups at solving problems and spotting external threats. Studies have also suggested that women are often better than men at building teams and communicating.

To make men feel even worse, researchers have also concluded that women make better investors than they do. A survey by Digital Look, a British financial website, found that women consistently earn higher returns than men. A survey of American investors by Merrill Lynch examined why women were better at investing. Women were less likely to “churn” their investments; and men tended to commit too much money to single, risky ideas. Overconfidence and overtrading are a recipe for poor investment returns.

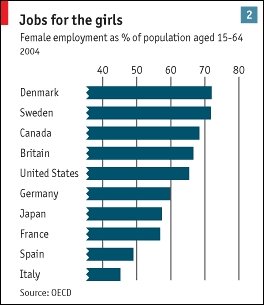

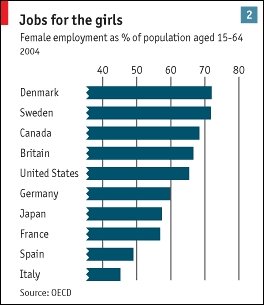

Despite their gains, women remain perhaps the world's most under-utilised resource. Many are still excluded from paid work; many do not make best use of their skills. Take Japan, where only 57% of women work, against 65% in America (see chart 2). Greater participation by women in the labour market could help to offset the effects of an ageing, shrinking population and hence support growth. Ms Matsui reckons that if Japan raised the share of working women to American levels, it would boost annual growth by 0.3 percentage points over 20 years.

women work, against 65% in America (see chart 2). Greater participation by women in the labour market could help to offset the effects of an ageing, shrinking population and hence support growth. Ms Matsui reckons that if Japan raised the share of working women to American levels, it would boost annual growth by 0.3 percentage points over 20 years.

The same argument applies to continental Europe. Less than 50% of Italian women and only 55-60% of German and French women have paid jobs. But Kevin Daly, of Goldman Sachs, points out that among women aged 25-29 the participation rate in the EU (ie, the proportion of women who are in jobs or looking for them) is the same as in America. Among 55- to 59-year-olds it is only 50%, well below America's 66%. Over time, female employment in Europe will surely rise, to the benefit of its economies.

In poor countries too, the under-utilisation of women stunts economic growth. A study last year by the World Economic Forum found a clear correlation between sex equality (measured by economic participation, education, health and political empowerment) and GDP per head. Correlation does not prove the direction of causation. But other studies also suggest that inequality between the sexes harms long-term growth.

In particular, there is strong evidence that educating girls boosts prosperity. It is probably the single best investment that can be made in the developing world. Not only are better educated women more productive, but they raise healthier, better educated children. There is huge potential to raise income per head in developing countries, where fewer girls go to school than boys. More than two-thirds of the world's illiterate adults are women.

It is sometimes argued that it is shortsighted to get more women into paid employment. The more women go out to work, it is said, the fewer children there will be and the lower growth will be in the long run. Yet the facts suggest otherwise. Chart 3 shows that countries with high female labour participation rates, such as Sweden, tend to have higher fertility rates than Germany, Italy and Japan, where fewer women work. Indeed, the decline in fertility has been greatest in several countries where female employment is low.

It seems that if higher female labour participation is supported by the right policies, it need not reduce fertility. To make full use of their national pools of female talent, governments need to remove obstacles that make it hard for women to combine work with having children. This may mean offering parental leave and child care, allowing more flexible working hours, and reforming tax and social-security systems that create disincentives for women to work.

Countries in which more women have stayed at home, namely Germany, Japan and Italy, offer less support for working mothers. This means that fewer women take or look for jobs; but it also means lower birth rates because women postpone childbearing. Japan, for example, offers little support for working mothers: only 13% of children under three attend day-care centres, compared with 54% in America and 34% in Britain.

Despite the increased economic importance of women, they could become more important still: more of them could join the labour market and more could make full use of their skills and qualifications. This would provide a sounder base for long-term growth. It would help to finance rich countries' welfare states as populations age and it would boost incomes in the developing world. However, if women are to get out and power the global economy, it is surely only fair that men should at last do more of the housework.

April 12, 2006

A guide to womenomics

The future of the world economy lies increasingly in female hands

“WHY can't a woman be more like a man?” mused Henry Higgins in “My Fair Lady”. Future generations might ask why a man can't be more like a woman. In rich countries, girls now do better at school than boys, more women are getting university degrees than men are and females are filling most new jobs. Arguably, women are now the most powerful engine of global growth.

In 1950 only one-third of American women of working age had a paid job. Today two-thirds do, and women make up almost half of America's workforce (see chart 1). Since 1950 men's employment rate has slid by 12 percentage points, to 77%. In fact, almost everywhere more women are employed and the percentage of men with jobs has fallen—although in some countries the feminisation of the workplace still has far to go: in Italy and Japan, women's share of jobs is still 40% or less.

The increase in female employment in developed countries has been aided by a big shift in the type of jobs on offer. Manufacturing work, traditionally a male preserve, has declined, while jobs in services have expanded. This has reduced the demand for manual labour and put the sexes on a more equal footing.

In the developing world, too, more women now have paid jobs. In the emerging East Asian economies, for every 100 men in the labour force there are now 83 women, higher even than the average in OECD countries. Women have been particularly important to the success of Asia's export industries, typically accounting for 60-80% of jobs in many export sectors, such as textiles and clothing.

Of course, it is misleading to talk of women's “entry” into the workforce. Besides formal employment, women have always worked in the home, looking after children, cleaning or cooking, but because this is unpaid, it is not counted in the official statistics. To some extent, the increase in female paid employment has meant fewer hours of unpaid housework. However, the value of housework has fallen by much less than the time spent on it, because of the increased productivity afforded by dishwashers, washing machines and so forth. Paid nannies and cleaners employed by working women now also do some work that used to belong in the non-market economy.

Nevertheless, most working women are still responsible for the bulk of chores in their homes. In developed economies, women produce just under 40% of official GDP. But if the worth of housework is added (valuing the hours worked at the average wage rates of a home help or a nanny) then women probably produce slightly more than half of total output.

The increase in female employment has also accounted for a big chunk of global growth in recent decades. GDP growth can come from three sources: employing more people; using more capital per worker; or an increase in the productivity of labour and capital due to new technology, say. Since 1970 women have filled two new jobs for every one taken by a man. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that the employment of extra women has not only added more to GDP than new jobs for men but has also chipped in more than either capital investment or increased productivity. Carve up the world's economic growth a different way and another surprising conclusion emerges: over the past decade or so, the increased employment of women in developed economies has contributed much more to global growth than China has.

Girl power

Women are becoming more important in the global marketplace not just as workers, but also as consumers, entrepreneurs, managers and investors. Women have traditionally done most of the household s

hopping, but now they have more money of their own to spend. Surveys suggest that women make perhaps 80% of consumers' buying decisions—from health care and homes to furniture and food.

hopping, but now they have more money of their own to spend. Surveys suggest that women make perhaps 80% of consumers' buying decisions—from health care and homes to furniture and food.Kathy Matsui, chief strategist at Goldman Sachs in Tokyo, has devised a basket of 115 Japanese companies that should benefit from women's rising purchasing power and changing lives as more of them go out to work. It includes industries such as financial services as well as online retailing, beauty, clothing and prepared foods. Over the past decade the value of shares in Goldman's basket has risen by 96%, against the Tokyo stockmarket's rise of 13%.

Women's share of the workforce has a limit. In America it has already stalled. But there will still be a lot of scope for women to become more productive as they make better use of their qualifications. At school, girls consistently get better grades, and in most developed countries well over half of all university degrees are now being awarded to women. In America 140 women enrol in higher education each year for every 100 men; in Sweden the number is as high as 150. (There are, however, only 90 female Japanese students for every 100 males.)

In years to come better educated women will take more of the top jobs. At present, for example, in Britain more women than men train as doctors and lawyers, but relatively few are leading surgeons or partners in law firms. The main reason why women still get paid less on average than men is not that they are paid less for the same jobs but that they tend not to climb so far up the career ladder, or they choose lower-paid occupations, such as nursing and teaching. This pattern is likely to change.

The fairer and the fitter

Making better use of women's skills is not just a matter of fairness. Plenty of studies suggest that it is good for business, too. Women account for only 7% of directors on the world's corporate boards—15% in America, but less than 1% in Japan. Yet a study by Catalyst, a consultancy, found that American companies with more women in senior management jobs earned a higher return on equity than those with fewer women at the top. This might be because mixed teams of men and women are better than single-sex groups at solving problems and spotting external threats. Studies have also suggested that women are often better than men at building teams and communicating.

To make men feel even worse, researchers have also concluded that women make better investors than they do. A survey by Digital Look, a British financial website, found that women consistently earn higher returns than men. A survey of American investors by Merrill Lynch examined why women were better at investing. Women were less likely to “churn” their investments; and men tended to commit too much money to single, risky ideas. Overconfidence and overtrading are a recipe for poor investment returns.

Despite their gains, women remain perhaps the world's most under-utilised resource. Many are still excluded from paid work; many do not make best use of their skills. Take Japan, where only 57% of

women work, against 65% in America (see chart 2). Greater participation by women in the labour market could help to offset the effects of an ageing, shrinking population and hence support growth. Ms Matsui reckons that if Japan raised the share of working women to American levels, it would boost annual growth by 0.3 percentage points over 20 years.

women work, against 65% in America (see chart 2). Greater participation by women in the labour market could help to offset the effects of an ageing, shrinking population and hence support growth. Ms Matsui reckons that if Japan raised the share of working women to American levels, it would boost annual growth by 0.3 percentage points over 20 years.The same argument applies to continental Europe. Less than 50% of Italian women and only 55-60% of German and French women have paid jobs. But Kevin Daly, of Goldman Sachs, points out that among women aged 25-29 the participation rate in the EU (ie, the proportion of women who are in jobs or looking for them) is the same as in America. Among 55- to 59-year-olds it is only 50%, well below America's 66%. Over time, female employment in Europe will surely rise, to the benefit of its economies.

In poor countries too, the under-utilisation of women stunts economic growth. A study last year by the World Economic Forum found a clear correlation between sex equality (measured by economic participation, education, health and political empowerment) and GDP per head. Correlation does not prove the direction of causation. But other studies also suggest that inequality between the sexes harms long-term growth.

In particular, there is strong evidence that educating girls boosts prosperity. It is probably the single best investment that can be made in the developing world. Not only are better educated women more productive, but they raise healthier, better educated children. There is huge potential to raise income per head in developing countries, where fewer girls go to school than boys. More than two-thirds of the world's illiterate adults are women.

It is sometimes argued that it is shortsighted to get more women into paid employment. The more women go out to work, it is said, the fewer children there will be and the lower growth will be in the long run. Yet the facts suggest otherwise. Chart 3 shows that countries with high female labour participation rates, such as Sweden, tend to have higher fertility rates than Germany, Italy and Japan, where fewer women work. Indeed, the decline in fertility has been greatest in several countries where female employment is low.

It seems that if higher female labour participation is supported by the right policies, it need not reduce fertility. To make full use of their national pools of female talent, governments need to remove obstacles that make it hard for women to combine work with having children. This may mean offering parental leave and child care, allowing more flexible working hours, and reforming tax and social-security systems that create disincentives for women to work.

Countries in which more women have stayed at home, namely Germany, Japan and Italy, offer less support for working mothers. This means that fewer women take or look for jobs; but it also means lower birth rates because women postpone childbearing. Japan, for example, offers little support for working mothers: only 13% of children under three attend day-care centres, compared with 54% in America and 34% in Britain.

Despite the increased economic importance of women, they could become more important still: more of them could join the labour market and more could make full use of their skills and qualifications. This would provide a sounder base for long-term growth. It would help to finance rich countries' welfare states as populations age and it would boost incomes in the developing world. However, if women are to get out and power the global economy, it is surely only fair that men should at last do more of the housework.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home