Microfinance: Services The Poor Can Bank On

BusinessWeek

BusinessWeekMay 2, 2006

By Chris Farrell

With the help of philanthropists, banks, and others, these institutions help local economies by providing small loans and financial services

The global economy is on a roll. China, India, and many other developing nations are clocking astonishing rates of economic growth, pulling millions out of poverty, and swelling the ranks of the global middle class. Nevertheless, about half the world's population still lives on less than $2 a day. How to eliminate global poverty is the most important economic and social question of our time, but the answer is contentious.

In a simplified typology, there are essentially two camps when it comes to development strategies. Economists like Jeffrey Sachs want the major industrial nations to dramatically boost their foreign aid. Bold activists believe that only a substantial hike in foreign aid dollars will bring into reality the U.N.'s goal of slashing poverty in half by 2015.

Grand visions like that worry card-carrying skeptics. They argue that the lesson of the past half century and more than $1 trillion in aid is that big blueprints inevitably disappoint. Instead, this group favors encouraging thousands of small indigenous projects. Their catchphrase, in the words of William Easterly, a leading skeptic and development economist, is "the right plan is to have no plan."

MOVE TO PROFIT. Yet there is one approach that bridges both camps: microfinance. It's a bold plan that skeptic Easterly supports and a grassroots movement that visionary Sachs applauds. True, there's no magic bullet when it comes to economic development. But microfinance is working in many countries.

"Some of the most powerful social changes brought about by microfinance occur when a family is able to earn that little bit extra, enabling them to keep their kids healthy and in school, thus open the doors of economic opportunity to the next generation," says Caitlin Baron, director of the microfinance initiative for the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation.

Microfinance is essentially a system for providing small loans to poor entrepreneurs, typically self-employed and running a home-based business. Although most microfinance institutions are started with public or philanthropic money, or money from other sources, many eventually become self-sustaining, profit-making enterprises. "This is an area where you can do good while doing well," says Brigit Helms, senior adviser at the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) and author of Access for All: Building Inclusive Financial Systems.

The microfinance revolutionaries are now setting their sights on an even more ambitious goal, transforming it from a daring experiment into a Big Idea. The goal is to create a more professional, inclusive financial system that reaches deep into both rural and urban areas. At the same time, microfinance is moving past its small-business base to offer the poor a wide range of financial services, including savings, insurance, money transfers, and a broad array of loan options.

STRONG NUMBERS. "The big idea is that the poor need the same range of financial services the wealthy do," says Frank F. De Giovanni, deputy director at the Ford Foundation. "We're really trying to figure out how to get the poor into the financial mainstream."

The modern origins of microfinance date back to the mid-'70s. Among the key innovators was Professor Muhammad Yunus of Bangladesh (see BW Online, 12/26/05 "Muhammad Yunus: Microcredit Missionary"). He had the idea of making loans to the very poor, especially women. He started the Grameen Bank Project in 1976, and transformed it into a bank in 1983. According to the bank, it now has nearly 6 million borrowers -- 96% of them women -- and almost 2,000 branches in some 64,000 villages. The repayment rate for loans is 98%, and the bank has earned a profit every year but three since its inception (see BW Online, 12/26/05, Can Technology Eliminate Poverty?").

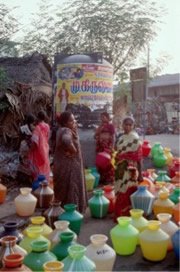

Microfinance institutions have sprung up throughout Asia, Latin America, Africa, East Europe, and elsewhere in the developing world. (They are also found in poor American communities and elsewhere in the industrial world.) These lending institutions range from tiny cooperatives serving a handful of villages to giant companies spanning a nation. Contrary to conventional banking wisdom, indigenous microfinance entrepreneurs have proved with their 92 million-plus customers, that the poor are bankable. "The leaders are indigenous players," says Helms. "It's local people taking a risk."

ROLE FOR BANKS. There is plenty of room for growth. Despite the rapid expansion of microfinance over the past 30 years, many poor families remain outside mainstream financial institutions. It's estimated that more than 75% of the world's 560 million poor families lack access to affordable financial services. That could change as the field attracts more capital, with international banks and the global capital markets putting capital into the business.

For example, some international banks are offering wholesale products and services to microfinance institutions. It's a low-risk way for a commercial bank to expand into a region's informal economy. A number of private funds have been created to invest in microfinance with money raised from well-heeled private investors. Governments and nongovernmental organizations are investing money and exper

tise to expand microfinance. Profit is critical for building sustainable microfinance institutions.

tise to expand microfinance. Profit is critical for building sustainable microfinance institutions.Philanthropy is a vital source of risk capital in this industry. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation gave $2.2 million over three years to the microfinance organization Opportunity International to develop a trans-African network of new commercial banks for the poor. The Gates Foundation also gave a $5.5 million grant to the Aga Khan Foundation USA for a microinsurance initiative in Pakistan and Tanzania. "It's a way to invest with a rate of return and achieve a social objective," says Frank De Giovanni. "The field needs more capital than it has."

URBAN PERSPECTIVE. Take the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation. It is concentrating its microfinance efforts on India, with a goal of investing substantial sums over the next 5 to 10 years in microfinance. Although there are about a dozen microfinance institutions in India, it's estimated that as little as a tenth of the potential market is being served. What's more, 90% of microfinance clients are in rural areas, even though 30% of Indians live in cities.

The Dell Foundation will concentrate on setting up business in six urban slums, Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore, and Hyderabad. (That is a total market of 18 million slum dwellers, including more than seven million children.) The foundation will provide "risk capital" and technical expertise and work with local microfinance entrepreneurs, as well as commercial and nongovernmental organizations. "For many of the microfinance institutions we fund, Dell Foundation support is essential to help get them off the ground," says Baron. "Once they are up and running, they are able to access commercial sector support."

The statistics about global poverty, from a lack of income, education, health-care, and other basic needs and wants is dismal. It's easy to despair. Yet there are reasons for optimism. One reason is the economic emergence of India and China. Another is the spread of microfinance.

Farrell is contributing economics editor for BusinessWeek. You can also hear him on Minnesota Public Radio's nationally syndicated finance program, Sound Money, as well as on public radio's business program Marketplace. Follow his Sound Money column, only on BusinessWeek Online

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home