Emerging From the Shadow of War, Sarajevo Slowly Reclaims Its Lost Innocence

The New York Time/Travel

February 5, 2006

By CHRISTOPHER SOLOMON

THE taxicab stops at the sign for the de-mining project. Five inches of fresh snow obscure the ground. Fikret, my Bosnian guide, leads me past blown-out houses, trenches in the woods, splintered bunkers, a Hapsburg-built tower from the 19th century accelerated to a ruin by war.

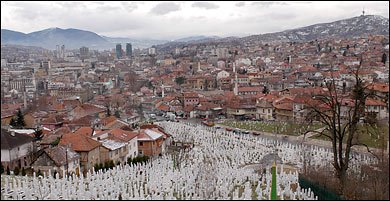

Then we are on the promontory looking over barbed wire down upon the city. Fikret points out the Kosevo Stadium, now nearly surrounded by cemeteries. Over there is Trebevic, he says. Once it was the site of the bobsled races. Now the mountain is divided between Bosnia and the Serb Republic, salted with mines, the run chipped with holes where the snipers once squinted over their rifles, stalking carelessness. Only from the hills does one grasp how pretty this city is, and how nakedly exposed it was.

It's easy to see, too, where the battle lines were set during the Serbs' 1,400-day chokehold on Sarajevo during the 1992-1995 war that convulsed the country: Look for the trees. Whenever defenders pushed back the aggressors, citizens weary of burning shoes and books for warmth clambered up to cut the pretty pine forests for firewood. Today the hills above Sarajevo, whose setting in the palm of enchanting mountains Rebecca West once likened to "walking inside an opening flower," wear a ragged Capuchin haircut.

Fikret Kahrovic was in the militia defending the city, but he does not offer much about the war, in a way that makes me think he could say plenty. He used to be angry all the time, he says, but not anymore.

"It was," he says, "like a very old and very bad movie that you watched once upon a time." His voice seems flat, affectless.

Then, as we stand looking over the city, Fikret says this: "One day it was 1992, August. I come to my home, was so tired, I laid on my sofa near my balcony, and five or six kids played table tennis on the street below. They were making so much noise — I was almost crazy! And soon there was an explosion. I ran to the balcony. They were all dead. I saw a child's brain on the asphalt. How do you make sense of that?" Then, as casually as if we had been discussing our lunch plans, Fikret stands me beside a war monument for a photograph.

In the picture I am squinting, confused, sharing the frame with the gilt names of the dead, unsure where to put my hands. It is my first full day in Sarajevo, in this country where history is never buried, and where moving on is a very complicated affair.

More:http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/05/travel/05sarajevo.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

February 5, 2006

By CHRISTOPHER SOLOMON

THE taxicab stops at the sign for the de-mining project. Five inches of fresh snow obscure the ground. Fikret, my Bosnian guide, leads me past blown-out houses, trenches in the woods, splintered bunkers, a Hapsburg-built tower from the 19th century accelerated to a ruin by war.

Then we are on the promontory looking over barbed wire down upon the city. Fikret points out the Kosevo Stadium, now nearly surrounded by cemeteries. Over there is Trebevic, he says. Once it was the site of the bobsled races. Now the mountain is divided between Bosnia and the Serb Republic, salted with mines, the run chipped with holes where the snipers once squinted over their rifles, stalking carelessness. Only from the hills does one grasp how pretty this city is, and how nakedly exposed it was.

It's easy to see, too, where the battle lines were set during the Serbs' 1,400-day chokehold on Sarajevo during the 1992-1995 war that convulsed the country: Look for the trees. Whenever defenders pushed back the aggressors, citizens weary of burning shoes and books for warmth clambered up to cut the pretty pine forests for firewood. Today the hills above Sarajevo, whose setting in the palm of enchanting mountains Rebecca West once likened to "walking inside an opening flower," wear a ragged Capuchin haircut.

Fikret Kahrovic was in the militia defending the city, but he does not offer much about the war, in a way that makes me think he could say plenty. He used to be angry all the time, he says, but not anymore.

"It was," he says, "like a very old and very bad movie that you watched once upon a time." His voice seems flat, affectless.

Then, as we stand looking over the city, Fikret says this: "One day it was 1992, August. I come to my home, was so tired, I laid on my sofa near my balcony, and five or six kids played table tennis on the street below. They were making so much noise — I was almost crazy! And soon there was an explosion. I ran to the balcony. They were all dead. I saw a child's brain on the asphalt. How do you make sense of that?" Then, as casually as if we had been discussing our lunch plans, Fikret stands me beside a war monument for a photograph.

In the picture I am squinting, confused, sharing the frame with the gilt names of the dead, unsure where to put my hands. It is my first full day in Sarajevo, in this country where history is never buried, and where moving on is a very complicated affair.

More:http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/05/travel/05sarajevo.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home