The Fever For Exotic Stocks

Simon Nocera runs a hedge fund that invests in emerging markets, and so, perhaps not surprisingly, prides himself on having a keen appetite for risk. But even he had to draw the line when his broker tried to get him into Zambian treasury bills.

"It was pure, baseless speculation," said Mr. Nocera, who has been investing in developing markets for more than 15 years. "If I am going to play the casinos, I would rather go to Las Vegas."

Mr. Nocera did not make the trade, but a number of his even more adventuresome peers did. Propelled by a boom in copper prices, Zambian government bonds, denominated in kwachas and yielding 25 percent for five-year paper, returned more than 40 percent this spring for those with a stomach strong enough for such a risky venture.

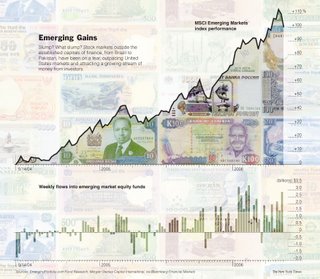

Four years into what has become the longest bull market in the brief, turbulent history of investing in emerging markets, investors from hedge funds to mutual funds to public and private pension funds have shown a willingness to take on increased levels of risk in developing markets. Benchmark stocks in the largest markets — like Brazil, Russia, India and China, collectively labeled B.R.I.C. — have experienced gravity-defying run-ups, prompting return-starved investors to look farther afield. Now in vogue are banks in the former Soviet republic of Georgia, airline companies in Kenya, oil refineries in the central Russian republic of Bashkortostan and start-up stockbrokers in India that go by the name of Indiabulls.

How short memories can be.

This week, a round of mini-devaluations in Turkey, South Africa and Indonesia was a reminder that emerging markets, despite their improving economies and stabilizing currencies, remain volatile and unpredictable. Seasoned investors note that while the Mexican devaluation of 1994, the Asian currency crisis in 1997 and Russia's default of its debt in 1998 were ultimately spawned by faulty policies in each country, the pandemic nature of these blow-ups was deepened by the panicked selling of unsophisticated investors.

Now, in the eyes of some, this combination of record capital inflows and indications that investors have once again have become indiscriminate in their buying, spells trouble.

For James Trainor, a portfolio manager at Newgate Capital in Greenwich, Conn., a leading emerging markets hedge fund, the sign that the fever for emerging market stocks was running too high came earlier this month when he overheard the short-order cook at his local diner debating which oil stocks in Venezuela he should be buying. "He was saying, 'Just wait until oil hits $100 — then these stocks will double,' " he recalled. "My reaction was: now things are really getting top-heavy."

Mr. Trainor, who manages more than $3 billion in assets and is a survivor of the previous decade's market meltdowns, sees other warning signs as well. "Brazilian banks are trading at five time earnings. Russian debt has become investment grade. The risks associated with international investing have been pushed aside because of the returns," he added, his voice rising to be heard above the din of a traffic jam in Mexico City, where he was calling from.

Despite the market turmoil this week, there is no indication yet that developing markets are prepared to collapse. Dollar reserves are at historic highs and the broad macroeconomic health of many of these countries is vastly improved, helped by soaring commodities prices and robust exports.

Indeed, these economies have undergone startling economic transformations. Not only do China and South Korea hold more than a trillion dollars in reserves between them, but companies like Gazprom in Russia and Samsung in South Korea have emerged as influential global conglomerates that are among the world's largest companies.

"The center of gravity has shifted," said Antoine van Agtmael, a long-time investor in developing economies, who coined the term emerging markets. "These countries have become creditors instead of debtors. Current-account deficits have become surpluses."

Nevertheless, the pell-mell rush of funds into these markets as well as the push for more exotic, riskier investment fare suggests that memories of past emerging market crises may have dimmed. Last week, funds that invest in emerging markets took in one of their highest weekly sums ever, bringing this year's figure to $33 billion, already outpacing last year's record $20 billion, according to EmergingPortfolio.com.

For hedge funds, always on the lookout for the next hot investment fad, it has been an opportunity not to be missed — 153 funds were formed last year to invest in emerging markets, according to Hedge Fund Research.

There is much anecdotal evidence to be found that shows how investing in emerging markets has evolved from a niche area for hardened globetrotters and steel-nerved investors.

In India, for example, a market that has shot up 141 percent over the last two years, some of the largest shareholders of top Indian companies are American mutual fund companies like Janus, known more for its momentum style of investing than for its emerging markets expertise.

Just as technology stocks were good to Janus in the late 1990's, so have Indian stocks been this time around. In the foreign large-growth mutual fund category, according to Morningstar, the top three performing funds over a one-year period are all from Janus. And all three funds have Reliance Industries and Tata Steel, two Indian companies that have gone up 166 percent and 71 percent, respectively, as their top two holdings.

Bidding wars have broken out between hedge funds for Indian investing talent; investment banks like J. P. Morgan, with limited experience in India, are now marketing closed-end Indian real estate funds to their high-net-worth clients; and Arshad R. Zakaria and Vikram S. Pandit, both of whom rose to be top executives at Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley, respectively, formed funds to invest in India's private and public markets after leaving their old firms.

In Russia, where the stock market is up 150 percent over the last two years, investors have been piling into commodity-based stocks. Indeed, the excitement for Gazprom, whose shares are up 266 percent over the past year, has become such that James Cramer has begun to shout out the company's virtues on his "Mad Money" program on CNBC, while more sober-minded industry analysts talk of it becoming the world's first trillion-dollar company.

It is not just foreign money that is pushing up stocks abroad. In Pakistan, where suicide bombings remain a frequent occurrence in Karachi, the country's commercial center, an aggressive economic overhaul has lured billions of dollars from Pakistanis at home and abroad into the stock market. Since 2001, the stock market capitalization has exploded from $10 billion to its current $55 billion, and it has only been in the last six months that foreign investors have started to dip their toes back into the market.

Perhaps the broadest indicator that shows how comfortable investors have become with emerging market risk is the historically narrow interest rate spread that separates the government bonds of countries like Indonesia, Mexico, Turkey and Pakistan from United States Treasury bonds, long the paragon of risk-free investment. In the past, the gap separating the paper of emerging economies has been wide, reflecting the higher economic and political risk associated with these countries.

But as these countries have turned their economies around, narrowing budget deficits and accumulating current-account surpluses, their credit ratings have improved. In a curious reversal, many of these countries, in Asia especially, are now the largest buyers of the Treasury securities that the United States government has been selling as its own budget deficit has widened.

"For the first time in modern history, poor countries are financing the rich," said Marc Faber, a global investment analyst noted for his gloomy prognostications. "I would not rule out one day that Brazil will have a better credit rating than the U.S." As an example he cites the time this spring that the yield on 10-year Polish bonds actually fell below United States bonds of the same maturity — a highly unusual occurrence for an emerging market bond.

But with spreads widening, seasoned investors like Mr. Trainor worry that that the sudden influx of new money, especially from hedge funds, many of which now are among the largest shareholders of companies in Turkey, Argentina and Mexico, may not have the patience or experience to withstand the volatility of these markets.

"Shining returns have attracted all walks of investors like mosquitoes around a lamp post," said Mr. Trainor, this time in an e-mail sent from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. "For an asset class best left to dedicated investors, those that aren't afraid to kick the tires in some of the most remote parts of the world, these mosquitoes better be careful or they might just get zapped."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home